The Scott Family Graves

Professor Peter Garside gives an account of key burial sites relating to Scott and his family, with a view to religious and other circumstances underlying each, and including details of the hitherto neglected monument to Scott's daughters in Kensal Green Cemetery.

In view of recent interest in the monument to Sir Walter Scott's two daughters, Anne (1803-33) and Charlotte Sophia (1799-1837), in Kensal Green Cemetery, London, it seems a fitting time to review the larger history of burial sites relating to the Scott family. Viewed as a whole, one is first struck by the wide dispersal of surviving monuments: a factor which has encouraged some commentators to suspect an element of dysfunctionality in the situation. John Sutherland, for example, senses a wider cultural division in the separate burial places of Scott’s parents, the ‘strict’ Presbyterianism of his father finding a suitable resting place in Old Greyfriars Kirkyard, a culturally broader leaning to Episcopalianism in his mother a more fitting one at the newly-built St John’s Chapel in Princes Street. [1] Not dissimilarly, feminist interpreters today might sense a degree of patriarchal privilege in the grouping of Scott himself alongside his son and heir, Walter, and son-in-law Lockhart, in the splendid setting of Dryburgh Abbey, compared to the relatively modest, hard-to-find, and hitherto neglected tomb in Kensal Green. Further investigation however suggests more diverse reasons for such disparities, both in immediate terms and more broadly, the history of the graves in part reflecting a shift in burial customs from crowded inner-city churchyards to newer cemeteries in the early nineteenth century.

The accepted burial place of Scott’s father, Walter Scott, Writer to the Signet, is marked in Greyfriars Kirkyard by a partly upright headstone, with no discernible inscription, below which is placed a more modern horizontal plaque recording the event.

According to the Burial Register, his remains were deposited on 18 April 1799. As Scott noted in an MS memorandum of 1819: ‘Our family [was] heretofore buried in the Greyfriars’ churchyard, close by the entrance to Heriot’s Hospital, and on the southern or left-hand side as you pass from the churchyard’.

[2] As such, it has a clear view of the west end of the Kirk, though there is no larger monument suggesting anything like a pre-existing family burial site. As a regular attender of the church, and long-standing elder, it was only natural that Walter Senior should be interred there, within a few hundred yards of his home in George Square, perhaps having secured further burial rights for his family.

According to a letter of Scott himself to his brother Thomas in late December 1819, two of their siblings, Anne (1772-1801) and John (d. 1816) had already been buried in the same place, though the experience of the latter’s funeral had proved somewhat distasteful for him: ‘When poor Jack was buried in the Greyfriars churchyard, where my father and Anne lie, I thought their graves were more encroached upon than I liked to witness’ (Letters, 6.75).

Scott’s fictional account of the funeral of Mrs Margaret Bertram in Guy Mannering (1815), set in the early 1780s, offers a similarly jaundiced view, in describing the ragged ‘sable procession’ to the site and the grotesque nature of the family mausoleum decorated with ‘scythes and hour-glasses, and death’s-heads, and cross bones’: ‘Here then, amid the deep black fat loam into which her ancestors were now resolved, they deposited the body’.

[3] In addition to the overcrowding of such graveyards, with older corpses being smashed up as fresh graves were dug and coffins plundered for wood, by the 1820s in Edinburgh, there was also the fear of ‘resurrectionists’ plundering new graves to provide specimens for anatomical dissection. Two iron cages known as mortsafes were used to cover fresh graves in Greyfriars, while watch-groups were also formed to act as a deterrent.

Such considerations clearly helped determine Scott’s choice of St John’s Chapel, at the west end of Princes Street, as a suitable resting-place for his mother. As he wrote in another letter to Thomas, of 10 January 1820: ‘Her remains were deposited in the new burial ground annexed to the Episcopal chapel & close to the West church. It is a large one sufficient for two families under all the common casualties of life and much more effectually secured than our open place of sepulchre in the Greyfriars.’ (Letters, 6.107).

As Scott goes on to indicate, he had purchased one quarter of a larger plot of eight places from Robert Rutherford, the son of Daniel Rutherford, the latter being a half-brother of Scott’s mother, as a result of her father Professor John Rutherford having remarried. A second quarter had been secured at the same time on behalf of the Russell family (of Ashestiel), themselves related to the Rutherfords (and so Scotts) by marriage. These purchases were timely, the death of Scott’s mother on 24 December being preceded by those of Daniel Rutherford and his sister Christian (a close confidante of Scott as a young man) on the 15th and 18th respectively. In recording these earlier deaths, Scott took comfort in his letter to Tom on 23 December (Letters, 6.75) in the security of the new burial site (‘It is surrounded with very high wall, and all the separate burial-grounds …are separated by party-walls going down to the depth of twelve feet’), as well as in the prospect of his mother being reunited with her close family (‘so the brother and the two sisters, whose fate has been so very closely entwined in death, may not be divided in the grave’). The structure known as the Dormitory, on the east end of St John’s Church, is still intact, though building works presently prohibits entrance, and a standing stone has been added on the green in more recent times to commemorate that Scott’s mother lies there.

Further information concerning the original disposition of the ground and subsequent burials can be found in Richard D. Jackson’s excellent ‘Scott and St John’s’, published in the Club’s Bulletin for 1999/2000, partly incorporating materials garnered by C. S. M. Lockhart for his Centenary Memorial (1871).[4]

The issue of whether the choice of this site reflects a leaning towards Episcopalianism is more complex. Both Scott and his wife Charlotte are listed as members of the qualified Episcopal congregation of Charlotte Chapel, at the west end of Rose Street, effectively the forerunner of St John’s, and his children were baptised by Daniel Sandford, the incumbent in both chapels and eventually Bishop of Edinburgh. Familiarity with the social circle there, which included the Duke of Buccleuch and the banker Sir William Forbes, would no doubt have helped make the burial ground next to the new church (consecrated in 1818) in Princes Street congenial for Scott and his maternal relatives and might also have eased the way in securing a plot. However, there is no evidence of Scott having attended St John’s as a place of worship, and as to his mother his remark to Tom that among other advantages ‘It is also close to the West Kirk [i.e. St Cuthbert’s] where our mother latterly attended divine worship’ (Letters 6.107) would strongly suggest that she had remained loyal to the Presbyterian persuasion.

Scott’s determination to be buried himself in Dryburgh Abbey was long-standing, and based on rights once belonging to the Haliburton family on his father’s side. In 1728, Scott’s paternal grandfather, Robert Scott, tacksman of Sandyknowe, had married Barbara, daughter of Thomas Hamilton of Newmains, who had acquired lands containing Dryburgh Abbey in 1700 and in which he himself was buried in 1753. The lands then passed to his younger brother, Robert, born in 1718, who sold them to Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Tod in 1767, after which in 1783 they were acquired by the Earl of Buchan. Scott, in his ‘Ashestiel’ Memoirs of 1808, laments the profligacy of his great uncle, the seller, and affirms that his own father could have purchased the estate ‘with ease’, had he not been wrongly persuaded otherwise: ‘And thus we have nothing left of Dryburgh although my father’s maternal inheritance but the right of stretching our bones where mine may perhaps be laid ere any eye but my own glances over these pages.’[5]

From an early point Scott seems to have gone out of his way to affirm this right. Writing to his friend William Clerk in 1790, he describes a meeting with the Earl of Buchan, during which ancestry and the Abbey both featured: ‘Heard a history of all his ancestors … From counting of pedigrees good Lord deliver us! He frequented Dryburgh much in my grandfather’s time.’ (Letters, 1.15). In the Grierson edition of the

Letters, this is footnoted with the text of a letter from Buchan several month afterwards to Scott’s uncle Captain Robert, of Rosebank near Kelso, stating that he has erected a tablet with a Latin inscription to mark the concession of burial rights in the Abbey to him and his two brothers, Thomas and Walter (Scott’s father). The plaque can still be seen bearing this inscription immediately behind the Scott family tombs in the North Transept in Dryburgh Abbey.

Given the circumstances, it is hard not to think that his nephew Walter was a main instigator here; and in the event Captain Scott was buried in the cemetery at Kelso Abbey, where Walter ‘Beardie’ Scott (Scott’s great-grandfather) also lies. Scott’s fixation also crops up during his courtship of his wife, when he envisages escorting her to ‘the ruins of an old Abbey’, where in due course ‘you must cause my bones to be laid’ (Letters, 1.83), a proposition somewhat amusingly countered by Charlotte in her reply: ‘What an idea of yours, was that, to mention ware you wish to have your bones laid, if you was married I should think you was tired of me, a very pretty compliment before Marriage’.[6]

At the time of securing his baronetcy, Scott moved further to secure the Dryburgh connection by having himself made legal heir to Robert Hamilton of Newmains, as stated in the ‘Preliminary Notice’ of his edition of

Memorials of the Haliburtons (1820): a publication which also included a frontispiece sketch by James Skene of ‘their Burial Aisle in the chancel of the Abbey-church’.

By the time Thomas Moore visited Dryburgh Abbey in 1825, on his way to Abbotsford, preparations were at least partly underway: ‘The vault of Sir Walter Scott’s family is here. Lord Buchan’s own tombstone ready placed, with a Latin inscription by himself on it, and a cast from his face let into the stone.’[7] The first use of the grounds however came as a result of the death of Charlotte, Lady Scott, in 1826, whose funeral was conducted according to the English service by Edward Bannerman Ramsay, who had come to Edinburgh in 1824 as a curate at St George’s Episcopal Chapel, in York Place, where Lady Scott (and also possibly Scott himself) had attended when in town. In the immediate aftermath, Scott took comfort in the fact that his own servants had mounted a protective guard over the grave. Following that was the funeral in a separate place of the Earl of Buchan in 1829, at which according Scott’s journal entry of 25 April, on it being noticed that the body had been placed in the grave with its feet pointing westward, he had quietly observed ‘that a man who had been wrong in the head all his life would scarce become right headed after death’.[8] Scott’s own much-reported funeral on 26 September 1832, including prayers at Abbotsford, and a long procession to Dryburgh, involved several clergymen, among them the Minister of St Cuthbert’s in Edinburgh, but it was the Anglican Rev. John Williams, under whose care Scott had committed his younger son Charles at St David’s College, Lampeter, and now rector of Edinburgh Academy, who read the burial service at the graveside.

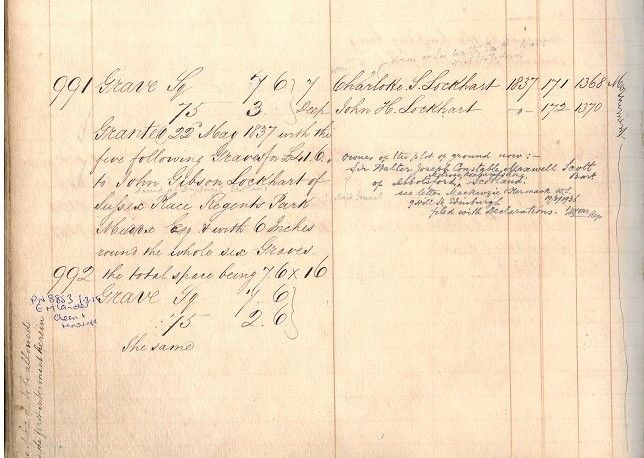

In the case of the burial of Scott’s daughters at Kensal Green, a new-found mobility offers the most concrete explanation. Late in 1825, John Gibson Lockhart had moved with his wife Charlotte Sophia (Scott’s elder daughter) to begin a new career as editor of the Quarterly Review, the family taking up residence at 24 Sussex Place, Regent’s Park. It was while Scott was recuperating in Naples that the couple suffered the death of their eldest son John Hugh Lockhart (the addressee of Tales of a Grandfather), who is registered as having been buried at St Marylebone Cemetery, Westminster, on 19 December 1831. In 1817 the new Church of St Marylebone had been built over a vaulted crypt which, consecrated in 1773, served as a burial ground until the early 1850s, by which time in its confines over 110,000 burials had taken place. Less than two years later the boy was followed by his aunt Anne (Scott), exhausted after having looked after both of her parents, who died on 25 June 1833 while living with the Lockharts aged only thirty. On 17 May 1837, John Gibson Lockhart was left as a widower with two young children following the death of his wife Charlotte Sophia. In this instance, Lockhart purchased space for six graves in the new Kensal Green Cemetery, consecrated as recently as All Souls Day 1832, and within striking distance of the Lockhart residence.

Writing to his sister Violet, he remarked: ‘I have purchased a plot of ground in the New Cemetery on the Harrow Road—a wide, spacious garden with a beautiful prospect—and that morning, an hour before we reach the spot, the bodies of Anne and Johnnie will have been removed thither from the vaults of Marylebone, that the sisters may be henceforth side by side, and the child in the same dust with the mother’. Aesthetics and spaciousness were clearly factors in Lockhart’s decision. As he continued to Violet: ‘except Westminster Abbey, there is no burial ground here that I could have been able to look at with comfort, and remember that it contained the ashes of my wife’.[9] Sophia’s service was conducted by the Rev. Henry Hart Milman, Canon of Westminster, reflecting Lockhart’s own espousal of the Anglican creed. On 29 May Lockhart wrote to the sculptor Sir Francis Chantrey, asking him to design a suitable monument:

It is in the new Cemetery on the Harrow Road & I had her sisters remains & her boy’s removed & placed the former beside her grave & the latter in it with her.

Now I am going to Scotland for some months & I shd like when I next revisit this spot to find the graves covered with stone coffins or the like of the plainest & least costly kind but still such as the eye might not dislike to dwell upon.[10]

Lockhart also enclosed inscriptions for the same, though these are not found with the surviving letter. The single chest tomb as now found has recessed panels to the north and south side containing inscriptions which read: ‘ANNE SCOTT, DAUGHTER OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, OF ABBOTSFORD BARONET, DIED JUNE THE 25TH 1833, IN HER 31ST YEAR’ and ‘CHARLOTTE SOPHIA, WIFE OF J. G. LOCKHART ESQ, AND DAUGHTER OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, OF ABBOTSFORD BARONET, DIED MAY THE 17TH 1837, IN HER 38TH YEAR, HER SON JOHN HUGH LOCKHART, DIED DECEMBER 16TH 1831, IN HIS ELEVENTH YEAR.’ In the same proximity can be found monuments relating to the politician Sir Matthew White Ridley and publisher John Murray II. The reputation of Kensal Green reached a highpoint in 1843 as a result of the decision of the Duke of Sussex, Queen Victoria’s uncle, to be buried there, rather than in the Royal vault at Windsor.

It is also apparent from Lockhart’s purchase of six places in Kensal Green that he foresaw himself and possibly his two surviving children also being placed there. His own actual burial alongside Scott at Dryburgh then might be seen as a product of immediate circumstances rather than long-standing intent. With the death of his surviving son, Walter Lockhart Scott in 1853, Abbotsford passed to his daughter, Charlotte Harriet Jane Lockhart, who had married James Robert Hope-Scott at an early age. It was during a stay at Abbotsford that Lockhart died on 25 November 1854, and was buried in the Abbey next to his father-in-law. Three years later, Hope-Scott, a follower of John Henry Newman, had converted to Roman Catholicism, though Lockhart had hoped that he would abide with the Church of England. On 26 October 1858, Mrs Hope-Scott tragically died from illness, followed within the same year by her baby daughter and son. All three were buried in the vault of St Margaret’s Convent chapel, a Catholic foundation officially opened in 1835, which now forms part of the Gillis Centre in Bruntsfield, Edinburgh. In the case of James Hope-Scott, who died in 1873, his coffin was brought up from London to its final resting place, a facility not so available during the earlier period under view. The sermon in London was given by Cardinal Newman; that in St Margaret’s chapel by the Rev. William J. Amherst, S.J.

One remaining death within the above timeframe was that of Scott’s younger son, Charles (1805-41), a career diplomat, whose remains lie in an antechamber, and is marked by a plaque, in the

Church of Saints Thaddeus and Bartholomew, a mile or so from the British Legation in Tehran. In more recent times, Dryburgh Abbey re-established itself a resting place for Scott’s descendants, the most recent burials there being those of the sisters Patricia and Dame Jean Maxwell-Scott, in 1998 and 2004 respectively, whose tombstone is in an enclosed grassy space slightly behind the main North Transept.

[1] The Life of Sir Walter Scott. A Critical Biography (Oxford 1995), 8.

[2] The Letters of Sir Walter Scott, ed. H. J. C. Grierson and others, 12 vols (London 1932-37), 6.75n. Henceforth cited as Letters, with references given in parentheses within the main text.

[3] Guy Mannering, ed. P. D. Garside (Edinburgh, 1999), 216-17.

[4] The Edinburgh Sir Walter Scott Club Bulletin, 1999/2000, 11-23; C. S. M. Lockhart, The Centenary Memorial of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. (London, 1871), 49-52, plus Plate XII, ‘Plan of the Episcopal Church and Burial Ground of St. John, Edinburgh, June, 1870’.

[5] Scott on Himself, ed. David Hewitt (Edinburgh, 1981), 5.

[6] Edgar Johnson, Walter Scott: The Great Unknown, 2 vols (London 1970), 1.153.

[7] Memoirs, Journal, and Correspondence of Thomas Moore, 8 vols (London, 1853-56), 4.330.

[8] The Journal of Sir Walter Scott, ed. W. E. K. Anderson (Edinburgh, 1998), 619.

[9] Andrew Lang, The Life and Letters of John Gibson Lockhart, 2 vols (London, 1897), 2.176.

[10] National Library of Scotland, MS 20437, f. 53. Thanks are due to the Trustees of the Library for permission to cite materials in their care.