Colloquium on Ivanhoe

15th August 2020

Kirsty Archer-Thompson gave us an exclusive guide to the artefacts held at Abbotsford relating to Ivanhoe

Kirsty Archer-Thompson F.S.A. Scot is Collections and Interpretation Manager for the Abbotsford Trust, the independent charity responsible for safeguarding and managing the former home and estate of Sir Walter Scott: a grade A listed house and designed landscape near Melrose in the Scottish Borders. She is responsible for managing the built and natural heritage of the site, including conservation, research and collections management, alongside the interpretation of the house as Scott's self-styled ‘museum for living in’, heading up a small team of core staff and seventy volunteers. Kirsty is presently leading a major cataloguing project on the Scott family archive and acting as educator on the Massive Online Open Course: Walter Scott - The Man Behind the Monument in association with the University of Aberdeen. She is a Council Member of The Edinburgh Sir Walter Scott Club and National Project Manager for Scott’s 250th anniversary across 2021 and 2022.

Sir Walter Scott and the Medieval Revival

My first encounter with Scott was a chance meeting. Long before I started working for Abbotsford, I bumped into Scott quite unintentionally as a fellow medievalist. At the time I was working on transcribing and studying a selection of medieval texts in what is known as the ‘Heege manuscript’ (MS Advocates 19.3.1), now held at the National Library of Scotland. This collection is a household miscellany of the late 15th century, probably originating from Derbyshire. Who should have acquired it for the Advocates Library in Edinburgh in the winter of 1806 but the Library’s Curator, Walter Scott (with a significant helping hand from the poet Robert Southey). Scott even went to the trouble of adding a contents list to the manuscript. At that point if someone had told me I would be looking after Scott’s astonishing home and collections one day, I would have assumed you were pulling my leg. A stroke of destiny, perhaps!

Abbotsford offers a medievalist a real feast for the senses. Scott was very much a product of his time and its fascination with other times. It was a melting pot of ideas and influences. The Gothic revival in the second half of the 18th century and its impact on architecture, antiquarianism and medieval literature; the overarching Romantic movement and its interest in the vernacular and a return to simpler, pre-industrial times, and indeed all of the published histories and philosophical works of the Enlightenment…. all of this intersected in an explosion of interest in medieval romance between 1790 and 1820 – which is, of course, the bicentenary year of Ivanhoe if we believe the title page (like a number of Scott’s novels, Ivanhoe was published in December and the publishers pre-empted the turn of the new year).

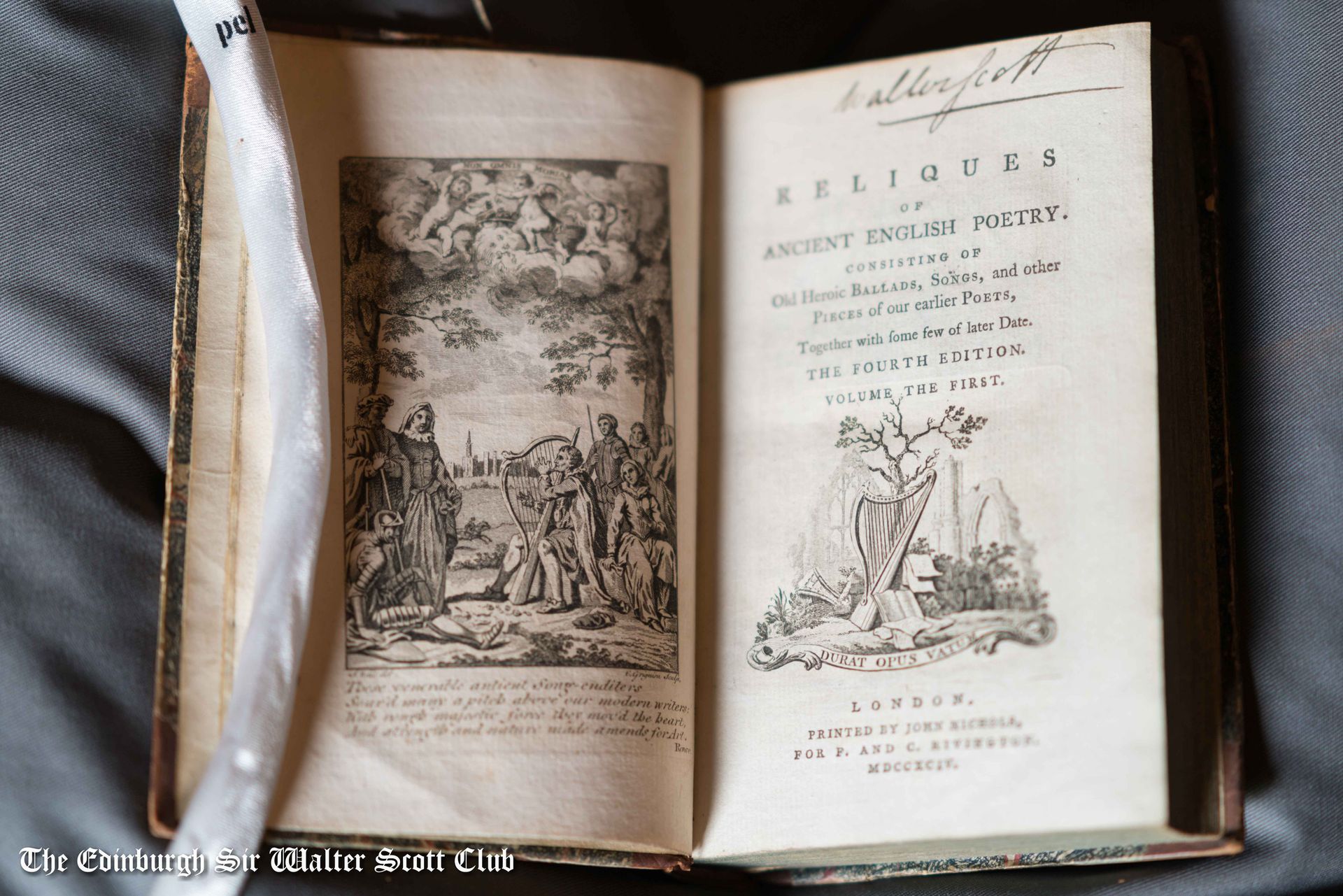

The Library Holdings

If we are looking for a single landmark publication that represents the enthusiasms of this age, then there is no better example than Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, first published in 1765. If any of you have the chance to go to Kelso, which is my hometown, you can walk along the riverside towards Mayfield and see the site of the plane tree under which the eleven-year-old Walter Scott first lost himself in this work. Actually the ballads and songs it contains come from both sides of the border and some date from as early as the 14th century. It was this work that reintroduced the ballad form and its historical and romantic subject matter to the reading public, and it was lapped up. This edition isn’t the one that was in Scott’s young hands under that shady tree, but the fourth edition purchased for Scott’s Abbotsford Library. One of many ballads it contains is Robin Hood and Guy of Gisbourne.

From his earliest days as a poet, Scott was also a respected medievalist familiar with a great many of the rediscovered texts of the period, via contemporary editions if not in the original middle English or French. One of his greatest friends, George Ellis, was one of the most esteemed medievalists of the age. Together they corresponded voluminously about Scott’s great contribution to the world of medievalism – his 1804 edition of the 13th-century romance Sir Tristrem, the very first ever published. If the name sounds familiar, this is because this is the only middle English variant of the popular love story of the Cornish Tristan and the Irish princess Isolde. Tristrem’s adventures as a knight involve numerous heroic quests, which include avenging his father’s death and killing an Irish half-giant. There is even a dragon fight for good measure.

The Abbotsford Library is incredibly well stocked with editions of medieval romances and indeed manuscripts of texts produced by individuals such as George Ellis. Many are held in the bow window of the room, in press N, one of only four which are still fitted with locks dating back to 1824. These cabinets were where Scott shelved some of his most prized and valuable books.

Andrew Lang once said that what Scott did so successfully was “make the new world listen to the accents of the old.” And that is very true of his particular brand of medieval revival. What Scott does so successfully throughout his poems and novels is breathe new life into some of the structures, motifs and stories of medieval romance that had enchanted him from childhood. Think of the many times in his novels that our hero is disinherited, or sent away into exile, or, in Ivanhoe, the use of disguise and the three-day jousting tournament. All of these devices have their foundations in medieval romance.

The Interior Decoration of Abbotsford

This isn’t just about the contents of the Library, of course. The enthusiasm for the medieval infuses Abbotsford at every level. Look above us at what is often known as ‘The Rosslyn Drop,’ a cast of the Nativity or Star of Bethlehem pendant from Rosslyn Chapel. But in Scott’s version of the scene, not all is as it seems. The three kings prevail but the shepherds with their crooks have become skeletal figures. What on earth can this mean?

Three kings or noblemen confronting three corpses whilst out hunting was a popular memento mori story of the Middle Ages known as the ‘Three Living and the Three Dead’, reinforcing the message that such as we are, so will ye be. The introduction of the virgin and child into this happy scene seems like a jarring meld, but not when you consider that versions of this story in art and literature would often appear alongside overtly religious images or texts. The carving is like a three-dimensional medieval miscellany all of its own and Scott loved this detail so much that it appears no less than three times within the interiors of Abbotsford, above the chandelier in the Drawing Room and right at the top of the attic stairway. As is well documented, the rest of the Abbotsford interiors are festooned with figurative and botanical details from Melrose Abbey, most of which are 15th century in date.

A Pilgrim Telling Tales

It's difficult to begin to think about medieval literature without thinking of Geoffrey Chaucer. Here are the pilgrims of his Canterbury Tales, in an exquisite engraving after Thomas Stothard’s 1806 painting in the form of an elongated frieze. This image has been above the fireplace in Scott’s Study since 1824, the year the interior was completed, and, under the illumination of the gasolier above his desk it was this image above everything else in the Abbotsford art collection that was closest to Scott as he set about the task of writing.

This choice has always intrigued me although it’s important to understand that this engraving was wildly popular in country houses of the period for all of the reasons we have already touched upon. Scott’s literary debt to Chaucer is well-established. The motif from the Knight’s Tale, his personal favourite, of two men vying for a lady’s hand often appears as a mirror image in Scott’s novels with two ladies and one ‘hero’ figure (think of Rose and Flora in Waverley or Rebecca and Rowena in Ivanhoe).

Scott had known the Canterbury Tales since youth but in editing the works of John Dryden, he also knew the stories intimately through this prism. Scott’s poetry often uses Chaucerian echoes in structure, form or language. He talked of his astonishment that all of Chaucer’s pilgrims seemed to have so much vitality in such an early text. That seems to me to be the central takeaway from this image. There is a great deal of life and movement and a real breadth in the characterisation; it’s a fascinating composition to really look at. But there is something else to note. What do the pilgrims actually do? They tell each other stories on the road to their destination. And isn’t that a very apt metaphor for how Scott lived? Moving through life with the irresistible compulsion to tell stories to an eager audience? I think Scott is casting himself as another pilgrim and as a teller of tales.

‘Mr Chainmail’

In collecting more broadly, Scott’s primary interest was arms and armour, a passion bordering on an obsession that he was well known for. In fact, in a satirical novel of 1831 called Crotchet Castle by Thomas Love Peacock, the character Mr Chainmail, a devout medievalist and castle owner, was intended to evoke Sir Walter Scott!

In the Monastery, one of my personal favourites of all the Waverley Novels, Scott describes Edward Glendinning as “a loaded hackbut which will stand in the corner as quiet as an old crutch until ye draw the trigger. And then there is nothing but flash and smoke.” A hackbut (and many other variants of the same name) are very early firearms, long barrelled and muzzle-loaded. They were first used in Europe during the Hundred Years War of the 14th century, probably to bolster the effect of archers and crossbowmen, although their accuracy left a lot to be desired! And what should we have standing in the corner as quiet as an old crutch in Scott’s Entrance Hall but a hackbut….

This is, quite possibly, Scotland’s earliest gun and dates from the second half of the 15th century. It’s made of wrought iron, the barrel is over 1m long on its own and the stock is just an iron rod ending in a hook. But how did it fire? Well, there is a touch hole in the side of the barrel for lighting the gunpowder. There are some grooves around it which suggest there may have been a flash pan originally – to funnel the ignited powder to the touch hole. Incidentally this method did not always work - this is the original root of the saying ‘a flash in the pan’ and a soldier would have to repeat everything over. Hopefully then that would discharge the shot towards the target. This would all have to be done whilst propping up the weapon on a support. This is just another example of how special Abbotsford’s militaria collections are and why Scott was revered by contemporary authorities on the subject such as Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick, one of the founding collectors of what is now the world-famous armour of the Wallace Collection.

But we can’t think about Scott and medievalism without acknowledging what he has placed in recreations of some of the saint’s niches from Melrose Abbey: two near-complete suits of armour. Let us focus on the suit on the right-hand side. In April 1819, in very poor health with gallstones and prior to signing the contract for Ivanhoe, Scott writes “I see Mr Bullock (and by that he means William Bullock of the Egyptian Hall Museum) advertises his museum for sale. I wonder if a good set of real tilting armour could be got cheap there.” And here we have a good set of real tilting armour or plate armour for the joust.

The tilt was the barrier that separated the two knights on horseback and prevented collisions. This type of ceremonial armour could weigh as much as 50 kilos, the average weight of a teenager, just to put that in context! The enlarged pauldron or shoulder plate is the tell-tale sign of its purpose, to help brace against the impact of the opponent’s lance blow. Manoeuvrability is highly restricted. This is the kind of armour worn in the early 16th century, the heyday of the court joust rather than the medieval joust which had closer associations with cavalry combat practice.

What this does powerfully illustrate was that the colour and noise of the tournament was already fizzing around in Scott’s head before commencing the writing of Ivanhoe, and that acquisitions like this helped to fuel that creative fire as he reimagined Anglo-Norman England

The Ivanhoe Effect

Ivanhoe and its specific brand of medievalism was a run-away success - the cherry on the cake for the appetites of the age and the hunger for national mythology. It was a mainstay of the stage and in 1826, Scott found himself watching a French operatic adaptation of his novel in Paris. Ivanhoe, of all the Waverley Novels, has perhaps had the most successful afterlife on the silver screen. And standing here, in front of the most medieval of all views at Abbotsford where the house behind me evokes twelfth-century castle rather than comfortable state of the art Georgian home, I hope I have given you some indication of how much Scott was a product of a spirit of the age, and by association, how his literature was shaped and inspired by his surroundings here at Abbotsford.