Edinburgh Locations and the Production of the Waverley Novels

Professor Peter Garside describes key places within a narrow space of Edinburgh in which Scott's Waverley novels were originally produced, with links to sites since lost and photos of current locations.

Considering the huge international success achieved by the Waverley novels of Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), it is remarkable how much of this was generated in a relatively small area of Edinburgh, originally centred on the High Street in the Old Town and the closes running off it. A central participant here was the bookseller Archibald Constable (1774-1827), the main publisher of nearly all Scott’s works of fiction to the mid-1820s, aided in this by his junior partner Robert Cadell (1788-1849). Having served his apprenticeship in the heart of the Edinburgh book trade, concentrated around the law courts in Parliament House, Constable in 1795 set up his own business on the north side of the High Street, specialising at first in old books (a sign above the door proclaiming ‘Scarce Old Books’, to distinguish the shop from nearby circulating libraries, though some wags at the time interpreted this as ‘Scarce O’ Books’). From this position Constable rapidly established himself a leading publisher in both Scottish and British terms, through entrepreneurial successes such as the Edinburgh Review launched in 1802 and the acquisition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1812. In the case of Scott’s second long poem, Marmion (1808), Constable offered Scott an unprecedented 1000 guineas for the copyright, exploiting this opportunity to demonstrate how upmarket imaginative works might be managed profitably from Edinburgh rather than London. In a letter of 2 May 1808 Scott’s fellow-poet James Hogg remarks how he had witnessed ‘240 copies of Marmion sold in Constable’s shop yesterday forenoon’.

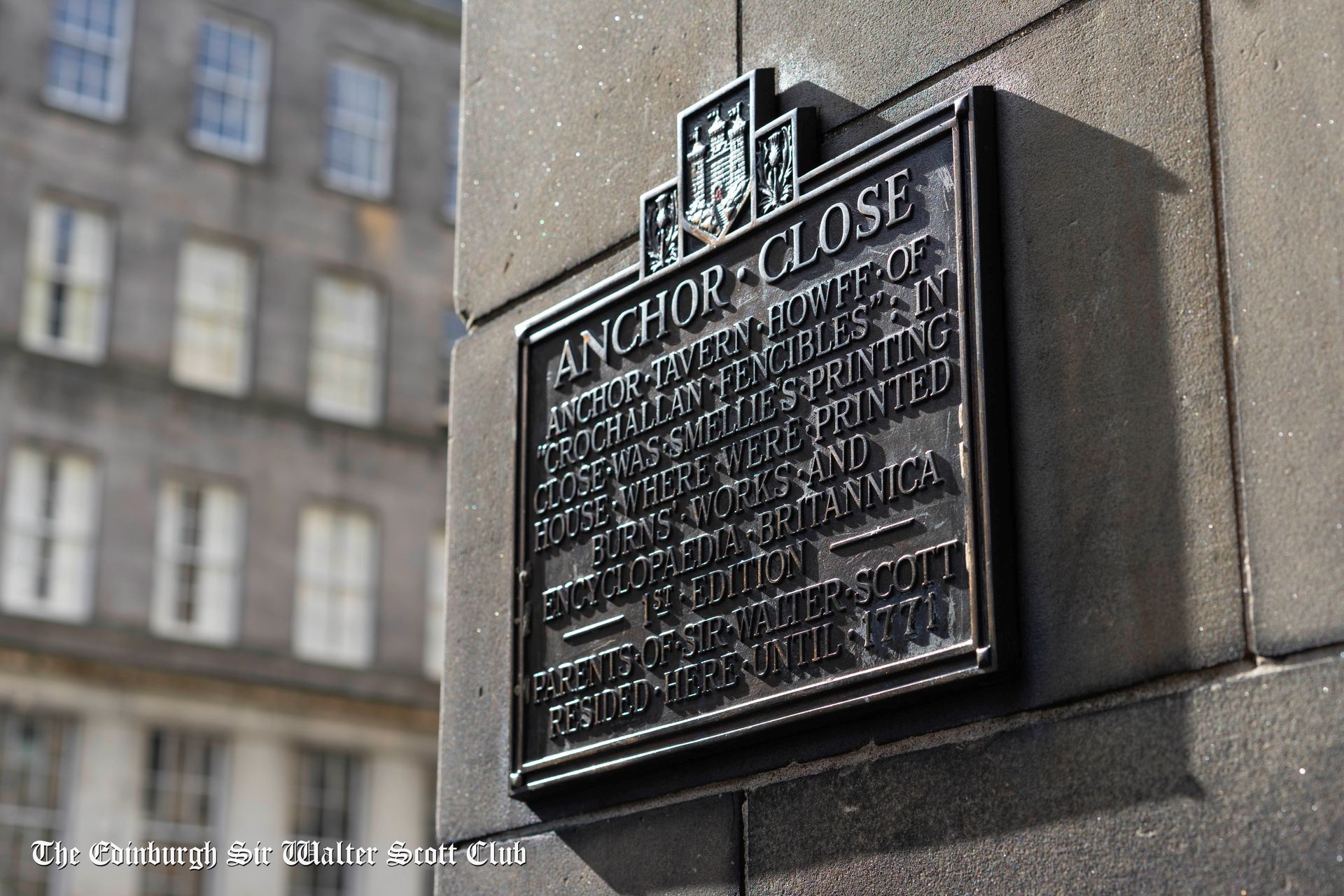

Early Post Office Directories describe Constable’s shop as at ‘the Cross’, this referring to the old Mercat Cross, which originally stood in the High Street below St Giles’ Cathedral (the site is now marked in the pavement), though ‘the Cross’ was also used more generally to denote the area between St Giles’ and the Tron Church. Later Directories give the address as 255 High Street, once part of a tenement building standing on the north side of the High Street (the present street numbering differs), subsequently demolished shortly after 1900 as part of the extension of the present-day City Chambers eastward. In Constable’s day this would have stood adjacent to the new Exchange building, erected in 1753 as an alternative the Mercat Cross for business transactions, as well as a number of busy closes, some now lost (the first presently surviving down the High Street being Anchor Close,

where Scott’s parents had lived early in their marriage, and at the foot of which stood the works of William Smellie, Robert Burns’s printer). Notwithstanding the retail sales witnessed by Hogg, Constable’s premises would have functioned increasingly as an administrative centre for an essentially wholesale operation. Scott’s son-in-law J. G. Lockhart in 1819 described the shop floor as ‘a low dusky chamber, inhabited by a few clerks’, with Constable himself preferring ‘to sit in a chamber immediately above, where he can proceed in his own work’. The concern maintained its commitment to the High Street until the early 1820s before moving to 10 Princes Street [photo shown underneath], close to the Register House, following a more general drift amongst booksellers towards the New Town.

Another key component was the nearby printing works of James Ballantyne (1772-1833), where all the Waverley novels were originally produced. Having printed some of Scott’s earliest works in his native Kelso, Ballantyne in 1802 decided to set up in Edinburgh, locating himself first in the precincts of Holyrood House, then in Foulis Close off the High Street, and finally at Paul’s Work at the North Back of the Canongate. In all this he received financial backing from Scott, who effectively became a hidden partner in the firm. Earlier Waverley novels (unusually) included Ballantyne’s name alongside the publisher on the title-page, while Edinburgh commonly appeared as the main place of origin, reflecting Scott’s deep sense of their Scottish manufacture. Originally a religious hospital for the poor, and later a workhouse, the building was first used to house Ballantyne’s presses in 1805, in what Scott in the following year described as ‘a hall equal to that which the Genie of the lamp built for Aladdin in point of size but rather less superbly furnished’. These presses were of the traditional wooden variety, normally operated by two men, and large numbers of staff, including compositors and proof readers, would have been engaged expediting Scott’s novels (usually comprising three volumes) for an expectant market. Whereas an inventory for 1806 lists twelve presses, by the 1820s more than twenty were engaged, as the impression number for first editions reached as high as 12,000. The most obvious route there from the High Street would have been down Leith Wynd: now no longer in existence, though its point of entry at the Netherbow is still represented by the west side of Jeffrey Street. Lower down from the Canongate, where Ballantyne’s private residence was located, it might be reached through Coul’s Close, one of several lanes then intersecting with the High Street.

Ballantyne’s house at 10 St John’s Street, since demolished, was one of a terrace of stylish houses, offering striking views of Salisbury Crags, whose past residents included the philosopher Lord Monboddo and (more briefly) Tobias Smollett, and in Ballantynes’s own day the novelist Mary Brunton and her husband. Now marked by its surviving entrance from south of the Canongate, the location provided Ballantyne easy access to Paul’s Work, where his printing office (reached through stairs at the side of the building) served as a focal point for many of the day-to-day business dealings relating to the novels. Nowadays his journey there can be paralleled by a walk of some five minutes down New Street, under the railway bridge, then left along Calton Road to a point (immediately beneath the old Calton Gaol)

from where the site of the works can be located to the left in yards now belonging to Waverley Station. In Scott’s time the site would have also allowed relatively easy access in the direction of Leith Docks, from where a large proportion of the Waverley novels were shipped in bales to be bound and marketed in London. Paul’s Work survived further in the nineteenth century, initially through Ballantyne being kept on as an employee after the failure of the firm in 1826, and was not removed by the North British Railway until the 1870s

Scott’s own Edinburgh residence from 1801 to 1826 was at 39 Castle Street, off Princes Street, in the New Town. It was here in a ground-floor study at the back of the house that large sections of the Waverley novels were written, including the last two volumes of Waverley, completed in a burst of several weeks in early summer 1814. As a Principal Clerk of the Court Session, during legal term times he also made regular carriage trips with his fellow Clerks up the Mound to the law courts in Parliament Square, placing him close to the nexus of operations at Constable’s shop. As an anonymous author, intent on keeping at one remove from the booksellers, however it was necessary to act stealthily, and many of negotiations concerning the contracting of his novels were carried out by John Ballantyne (1774-1821), James’s younger brother, who effectively became Scott’s literary agent after the failure of the publishing house of John Ballantyne & Co., another enterprise involving Scott. Numerous small notes relating to business deals between the Ballantynes and Scott’s publishers, many of which must have been by delivered by hand, have survived; and there is evidence enough too of the almost continuous first-hand meetings that must have taken place, whereby deals were struck, manuscripts transmitted, proofs exchanged, and profits calculated.

As a whole, it is hard to imagine a tighter nexus of relationships involving author, agent publisher, and printer. To some extent, this was dissipated in the 1820s owing to Scott’s growing preoccupation with the development his Border home at Abbotsford and the drift of the book trade in Edinburgh towards the New Town. A notable instance of the latter was William Blackwood’s move from premises at 64 Bridge Street (opposite the University Old College) to more fashionable quarters at 17 Princes Street, this occurring shortly after his having secured the contract to publish Scott’s fourth work of fiction, Tales of my Landlord (1816), the one new title to elude Constable’s grip. James Ballantyne for his part shifted his private residence to 3 Heriot Row, whereas his brother presided over auction rooms in Hanover Street. In the wake of Constable’s bankruptcy in 1826, Robert Cadell set up independently at 41 St Andrew Square, incorporated in a building on the east side of the square, once housing the National Bank, prior to its demolition in 1936 to make way for a headquarters for the Royal Bank of Scotland (now unoccupied).

It was from here that he orchestrated the Magnum Opus collected edition of the Waverley Novels (1829-33), as well as a sequence of other editions aimed at all levels of the early Victorian reading market. After Cadell’s death, the copyrights to the Waverley Novels were secured by the Edinburgh firm of Adam & Charles Black, who at the same time removed to 6 North Bridge to accommodate the resultant expansion of their output. In their hands production of Scott’s fiction remained a mainstay of the Edinburgh print industry until at least the end of the century, on a scale comparable to the magnificent Scott Monument that so visibly graces Princes Street today.

Professor Peter Garside © 2016.